How poultry and a pandemic put Tractor Supply ahead of the pack

A COVID-driven exodus of Americans to the country, along with unprecedented demand for chicks, goats, and other hobby livestock, made Tractor Supply one of the hottest retailers of 2020. Can it keep its place in the pecking order?

BY PHIL WAHBA

June 3, 2021

This article appears in the June/July 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, “Chicken coup.”

Hal Lawton is pushing poultry, literally and figuratively.

The boyish Tennessean leans over a stock tank that holds dozens of chicks; he gently nudges some of them out of his way so he can check the air coming out of the heater in the tank. The tiny birds are the star attraction of Tractor Supply Co.’s big annual “Chick Days” promotional event. And on a prematurely sultry April day at a brand-new store in Wappingers Falls, N.Y., Lawton, the retailer’s CEO, is making sure the babies are comfortable as they chirp and wait to be taken home.

For any customer, the chicks could be the start of a buying spree. On shelves nearby are starter kits that help beginner poulterers care for their birds. Each kit includes essentials like heat lamps and a chick feeder. Lawton explains another accessory to a novice observer: “This is to hold your eggs after they come out.” The chain recently started selling $1,300 brooder towers that keep chicks safe and warm. And just a couple of feet behind Lawton stands a six-foot-tall iron rooster—a whimsical decorative bargain at $160.

Tractor Supply, a 2,100-store retailer based near Nashville, is riding a backyard poultry craze. Last year it sold 11 million birds, including chickens, ducks, and turkeys—half of them to first-time customers who plan to raise them primarily for their eggs. “Everybody’s doing it,” says Lawton, so Tractor Supply is doubling down. “We want to dominate poultry,” the CEO says.

Birds are a small part of its business (chicks cost just a few dollars each), but those fledglings illustrate many of the things Tractor Supply does right. The chicks generate future spending on food and accessories. They’re intended to complement a rural lifestyle, rather than to wind up, say, covered in blue cheese at a Buffalo Wild Wings. And they’re the kind of hard-to-ship, hard-to-store item that giants like Walmart, Home Depot, or Amazon don’t deal with.

Fueled by such insights, Tractor Supply has generated a remarkable run of success, including at least 26 straight years of sales growth, out of a quirky but growing market niche. Founded in the 1930s to serve working farms, it has thrived by catering to hobbyist farmers—including suburbanites with larger properties who love gardening and dabble in livestock. Its midsize, carefully curated stores offer an eclectic mix of work clothes, tools, pet food, and feed for farm animals (especially chickens, goats, and horses). And those stores are concentrated in the exurbs—not deeply rural country, but at the edge of metropolitan areas, where backyards can be tallied in several acres. “They really understand their customer. They know where their customer lives and the lifestyle they lead,” says Joe Feldman, an analyst at research and trading firm Telsey Advisory Group.

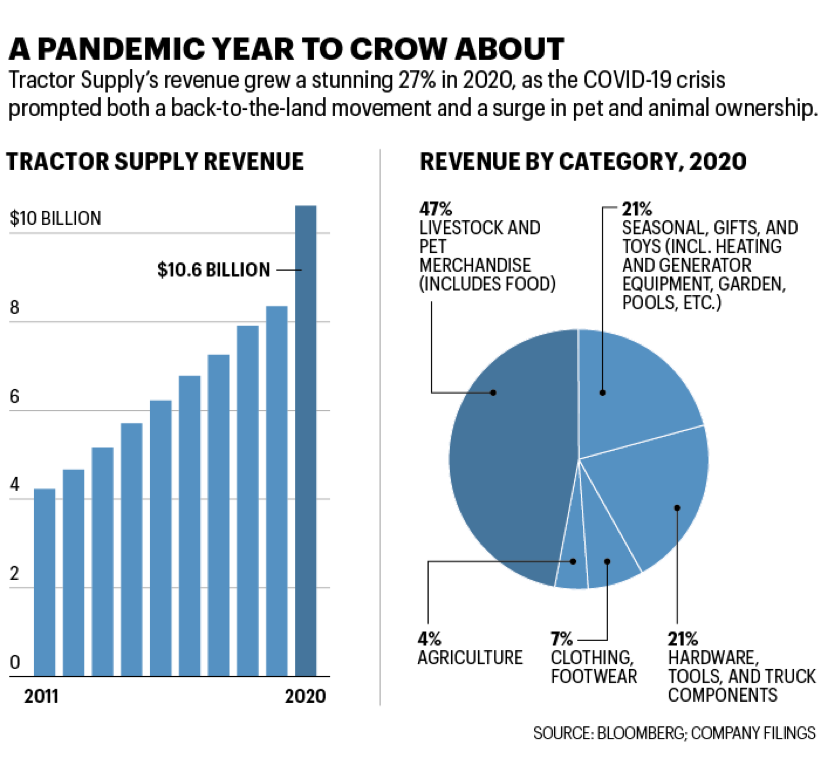

In 2020, Tractor Supply attracted a new wave of customers as the pandemic confined nearly everyone at home and persuaded more urbanites to try smaller-town living. Americans adopted pets by the millions, shifted spending to their homes—including their second homes—and sought solace in the outdoors. And Tractor Supply became one of the fastest-rising companies in the Fortune 500, jumping 89 spots to No. 291 on this year’s list on the strength of revenue that surged 27% in 2020, to $10.6 billion. (That momentum continued into 2021: Tractor Supply’s sales rose 43% year over year in the first quarter, with some help from stimulus checks.)

Such gangbusters growth is unlikely to continue, with the pandemic easing. But the rush to the country that underpins it is less an anomaly than a speeding up of a long-term trend, as more people—notably millennials yearning to become homeowners—look to adopt quasi-rural lifestyles. Being priced out of urban living is one driving factor; interest in healthier and more sustainable diets, including homegrown vegetables and home-harvested eggs, is another. Whatever is motivating them, Tractor Supply sees an opportunity in these “ruralpolitans”—and the COVID-driven shift toward remote work will help sustain their numbers.

Lawton, who became CEO in early 2020 after two years as the No. 2 at Macy’s, says millennials’ willingness to move farther from city centers is a “game changer”: “We’re seeing a new kind of shopper in our stores,” he tells Fortune. Now Tractor Supply is adapting to cater to both its established customer base and these younger space-seekers, following a strategic road map with the folksy title “Life Out Here.”

Staying at the top of the pecking order won’t be simple: To keep growing, the company will need to play catch-up on e-commerce and compete with much bigger retailers in areas like garden supplies and sporting goods. But Lawton and his team will be working from a successful, hard-to-imitate playbook—one that has them, for now, on a winning streak.

Most Tractor Supply stores don’t sell tractors, and its founder never worked a day of life on a farm. The company began in 1938 as a mail-order catalog, selling tractor parts. Charles Schmidt, a 26-year-old Chicago brokerage-house employee, established the company to serve frugal farmers struggling after the Depression, and it initially thrived as the “Sears of farm supplies.” The year after its founding, Tractor Supply opened its first store, in Minot, N.D.

Professional farmers originally made up 90% of Tractor Supply’s clientele; today that figure is 10%. Far fewer Americans farm today, as agriculture has consolidated and industrialized. But by the 1990s, the demographics of rural America had taken an interesting turn. During that decade, the number of rural route addresses grew 25%, as more people bought primary and weekend homes in the country rather than, say, at the beach. Since 2011, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, the population in rural areas at the edge of larger “metros” has slowly but steadily grown. And some of those back-to-the-landers are trying their hand at small-scale farming—raising eggs or goats or heirloom tomatoes for fun and, occasionally, for extra income.

Through the 20th century, Tractor Supply had maintained a steady but modest-size business, gradually selling more to rural homeowners and less to full-time farmers. It took 60 years for the retailer to reach the $500 million annual-sales milestone. But it took only 16 years to jump from there to the Fortune 500 (it debuted in 2014, with $5.7 billion in revenue), as the company hitched its wagon to the hobbyists.

Today, the core Tractor Supply customer typically has one to five acres of land, some small livestock like chickens, hogs, or sheep (in Texas, there could be a couple head of cattle), and perhaps a horse or two. “They’re not big industrial farmers—they live out here because it’s their passion,” says Tractor Supply’s senior vice president of marketing, Christi Korzekwa. The fast-growing new cohort that Tractor Supply is cultivating, she says, are “beginning to learn how to garden. They have this passion for poultry.” Call them the “country suburban” customers.

The company is strategic about where it meets these customers. Its stores are almost all located in mid-size or small towns—communities that are often too small to support a Home Depot, Petco, or Walmart. (A Telsey study a few years ago found that the typical Tractor Supply was a 30-minute drive from any of its major rivals.) Wappingers Falls, a hamlet of 5,500 souls 75 miles north of New York City, is a textbook Tractor town: It sits in the heart of Dutchess County, where many New Yorkers have weekend homes (some of which became primary abodes during the pandemic), but outside New York’s densely populated ring of commuter suburbs. The Tractor Supply there sits across Route 9 from a Mercedes-Benz dealership; the nearest Lowe’s is a few towns away.

11 million

CHICKENS, DUCKS, TURKEYS, AND OTHER FOWL SOLD BY TRACTOR SUPPLY IN 2020

Tractor Supply stores are almost identical in size, at 15,500 square feet—the average Home Depot or Lowe’s is six times as big. Tractor Supply’s strength lies in getting the product assortment just right given the small footprint. The layout is consistent from store to store: Immediately to the right upon entry are work apparel like gloves, Carhartt jackets and beanies (equally appropriate for the barn or the brewpub), Wrangler jeans, and cowboy boots—for the hobbyist rancher who’s perhaps more into the look than the work. Just past the clothes are the pet-supply area and animal victuals, in aisles dominated by enormous bags of horse, goat, chicken, and even alpaca feed. And close to that is the chicken section (lots of coops and heat lamps, but birds, beware: Tractor Supply also sells plucking and butchering equipment).

The store can be configured to give space to products according to local demand. In this section, Tractor Supply is careful to make sure its offerings don’t overlap much with rivals. For a portable propane tank for a gas barbecue grill, for example, you could shop at dozens of retailers; for a 100-pound propane tank for a welding project, Tractor Supply is the more likely go-to.

Much like specialty pet retailers, Tractor Supply is getting a tailwind from the pandemic surge in pet adoption. Overall, animal feed and agricultural products like fencing and fertilizer generate about half its net sales. Those staples are central to getting people into stores, where they might round out a shopping trip with a puppy chew toy or a baseball cap from the Kevin Costner TV ranch drama Yellowstone. “We want to get people in with their essentials, and then we can get the rest of the basket,” says chief merchant Seth Estep. That approach helps explain why Tractor Supply has managed to increase sales during each of the last three downturns, including the pandemic mini-crash: People feed their pets, and their livestock, through thick or thin.

In 2008, during the Great Recession, when Hal Lawton was an executive at Home Depot, he went on a reconnaissance mission with a colleague (Craig Menear, now Home Depot’s CEO) to understand why a smaller competitor was weathering the brutal climate so well. That competitor was Tractor Supply—and as the interlopers walked the floor of one of its stores, Lawton marveled at the company’s ability to choose just the right merchandise, and to be so precise in knowing how much to stock. The experience, Lawton recalls, instilled him with “admiration for not only the business model and the sustained performance, but also the culture.”

Lawton, now 46, has roots in Tractor Supply territory: He was raised in Kingsport, a town of about 54,000 some 100 miles northeast of Knoxville. He didn’t grow up with livestock, but many friends did, even though few lived on working farms. “Everybody up there had trucks and ATVs and animals,” recalls Lawton.

His own retail career has been more online than off-road. In the 2000s, Lawton played a key role in turning Home Depot into an e-commerce behemoth. By the time he left in 2015, the chain’s e-commerce had grown from almost nothing into a multibillion-dollar business; it now accounts for about 16% of sales. Lawton refined his e-commerce chops at eBay, where he spent the next two years, and then as president at Macy’s, an e-commerce leader among department stores. When Tractor Supply’s board came calling in mid-2019, Lawton was all ears: Macy’s was struggling, and Tractor Supply is based in his home state. But the farm-supply dealer also needed to build its e-commerce muscle, which made the fit even better for what would be Lawton’s first CEO job.

The COVID-19 outbreak struck just 10 weeks after Lawton took the reins. Tractor Supply, like many big-box chains, was deemed an essential retailer and thus could keep stores open. But that didn’t change the fact that shoppers didn’t want to crowd into stores and linger. Before the pandemic, the company had been working on curbside pickup for online orders: Under pressure, Lawton pushed the company to get the service up and running in just a few weeks. A year later, some 75% of online orders at Tractor Supply are picked up at the store.

The pandemic highlighted the prescience of the board in choosing a CEO with e-commerce know-how, but it also underscored one of Tractor Supply’s vulnerabilities. E-commerce as a share of net sales doubled in 2020—but only to 6%, far below many rivals. Because so many items Tractor Supply sells—think 80-pound bags of horse feed, or a riding lawn mower—are too big to be shipped without vaporizing profits, a lot of its business is “Amazon-proof.” But that also means the company can’t offer as much of the door-to-door convenience that its newer, urban-minded customers are accustomed to.

To keep e-commerce growing despite that handicap, Lawton is focusing on tech innovations that can keep customers engaged. Over the course of the pandemic, the company has revamped its website, with detailed product information and relevant search results that outdo what many competitors offer. “It’s not even comparable,” says Kathy Gersch, chief commercial officer at consulting firm Kotter, of the improved site. “They know the subject matter, and customers are going to trust an authentic source of information.” A typical Tractor Supply store carries up to 20,000 different items, but the company sells about 150,000 online: The hope is that its website improvements will draw customers to products that don’t normally sell well enough to command space in stores.

Tractor Supply’s recently relaunched loyalty program now has 20 million members, a figure comparable to much larger retailers. Part of sustaining that loyalty involves making its app smarter. If you buy a chick, the retailer’s new app can periodically suggest products to buy over the life of the bird. Tractor Supply’s website and app also offer tutorials on topics that require specialized expertise (think fence installation), and will soon connect customers one-on-one to on-staff professionals. “Sometimes you can only get so much out of YouTube, and you need to talk to a live person,” says technology, digital commerce, and strategy chief Rob Mills.

Lawton wants to make sure that more of those experts look like the country at large. Only 17% of Tractor Supply’s employees are members of minority groups, a potential Achilles’ heel at a time of deep demographic change in the U.S. Last summer the company hired its first diversity and inclusion director. “Our goal is for our stores and our team members to mirror the communities that we serve,” says Lawton.

Tractor Supply currently commands 16% of the fragmented “farm and ranch supplies” market, and Wall Street sees room to grow there. But to retain and build on its influx of newer ruralpolitan customers, the company aims to broaden the range of what it sells, even if it means competing with some of the big-box retailers with whom it hasn’t previously overlapped much.

Making better use of physical stores is key to that effort. At many stores, Tractor Supply is overhauling its “side lots”—5,000-square-foot adjacent areas that have largely been relegated to serve as storage or sales space for unexciting products like fencing. Lawton wants to use these lots to showcase items like patio furniture and gardening supplies, to boost the company’s appeal among less “farmy” suburb dwellers and women. (Women represent nearly half of Tractor Supply’s customers, up from 40% just a few years ago.) “Lawn-and-garden is the No. 1 category our customers play in but that we aren’t currently a destination for,” says Lawton.

“They know the subject matter, and customers are going to trust an authentic source.” Or as a Tractor Supply exec puts it, “Sometimes you need to talk to a live person.”

KATHY GERSCH, CHIEF COMMERCIAL OFFICER AT KOTTER, A CONSULTING FIRM

There are parts of the West and Midwest where Tractor Supply is largely absent, and Lawton sees room to add some 500 stores nationally over time. In perhaps the biggest bet of his tenure so far, Tractor Supply has agreed to buy Orscheln Farm & Home, a 167-store rival that’s big in Missouri, Kansas, and Iowa. If the Federal Trade Commission signs off, the $297 million acquisition will be Tractor Supply’s biggest ever. Orscheln is also a player in sporting goods, a category that Tractor Supply has long had its eye on, and the deal could help the company learn how to compete with the likes of Dick’s Sporting Goods or REI. “It will be a good thing for them to have a sandbox to experiment in,” says Kotter’s Gersch.

All the while, Tractor Supply continues to gussy up its stores—seeking that just-right balance between suburban impulse-buy appeal and rural practicality. It plans to add 125 shop-in-shops for Carhartt, for which it is the biggest retail partner, the better to attract both hipster newcomers and the laborers who actually work in the cool work wear. Other touches include $10 self-service dog washes, something that customers have been known to use for pets like goats and miniature ponies too.

The goal: Keep giving shoppers a reason to visit stores, even as their working and shopping lives move increasingly online. “What does a customer do after they wash their dog?” asks stores chief John Ordus. “They buy something new for the dog.” And maybe a semi-ironic baseball cap while they’re at it—or, if they’re feeling extravagant, a six-foot iron rooster.

This article appears in the June/July 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, “Chicken coup.”